Layout tools attempt to identify the best layout of wind turbines on a land or offshore area according to energy capture. They model free stream wind flowing through an area with sited turbines and calculate the energy output of successive turbines while taking wake effects and turbulence intensities into account. A key component of such tools is the ‘optimiser’ algorithm used to efficiently search through a modest proportion of candidate layouts to identify the best one. This article discusses earlier bio-inspired algorithms, and then the CMA-ES algorithm, an evolutionary algorithm that performs stochastic sampling optimisation by mimicking fundamental aspects of the neo-Darwinian evolutionary process.

Layout tools attempt to identify the best layout of wind turbines on a land or offshore area according to energy capture. They model free stream wind flowing through an area with sited turbines and calculate the energy output of successive turbines while taking wake effects and turbulence intensities into account. A key component of such tools is the ‘optimiser’ algorithm used to efficiently search through a modest proportion of candidate layouts to identify the best one. This article discusses earlier bio-inspired algorithms, and then the CMA-ES algorithm, an evolutionary algorithm that performs stochastic sampling optimisation by mimicking fundamental aspects of the neo-Darwinian evolutionary process.By Kalyan Veeramachaneni and Una-May O’Reilly, Evolutionary Design and Optimization Group, CSAIL, MIT, USA

{access view=!registered}Only logged in users can view the full text of the article.{/access}{access view=registered}The layout of turbines in large wind farms is challenging because of the larger farm and the additional turbines, feasibility constraints and wake model complexity. Due to the inherent complexity, bio-inspired algorithms such as evolutionary strategies (ES), genetic algorithms (GAs) and particle swarm optimisation (PSO) have been used for layout optimisation. Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) perform stochastic sampling optimisation by mimicking fundamental aspects of the neo-Darwinian evolutionary process. They simultaneously search with a ‘population’ of candidate solutions and associate an objective score as a fitness value for each one. They then select among the population to favour those solutions that are more ‘fit’. The next generation (i.e. a new population) consists of replicates of the fitter solutions which have been ‘genetically mutated and/or crossed over’ in a biological metaphor: the decision variables were perturbed such that they inherit some characters of their ‘parents’ as well as change in random ways.

One EA method subdivides the farm area into a grid of cells. The algorithm searches for which cells will have a turbine placed within. Because there is only one turbine per cell, a large cell respects turbine proximity constraints. However, the larger a cell, the lesser the degree of flexibility in turbine placement. An alternative proposes a turbine’s location as a decision variable pair of real-valued, spatial Cartesian (x,y) coordinates. With this representation, many more layouts are possible; however, the number that violate proximity constraints increases exponentially.Using (x,y) coordinates, PSO adapts each decision variable independently, and alters a turbine’s position independent of other turbines in the layout. A GA’s cross-over operator explores multiple subsets of decision variables simultaneously but, in both cases and when an ES is used, this increases proximity violations. Simple versions of these algorithms, when required to pack a large number of turbines in a relatively small area, inadequately navigate through the sparse and discontinuous feasible solution space.

In Optimizing the Layout of 1000s of Turbines in Proceedings of the Annual European Wind Energy Conference (EWEA), 2011, by Wagner, Veeramachaneni, Neumann and O’Reilly, we formulate a covariance-matrix-adaptation based evolutionary strategy (CMA-ES) which converges upon high performing turbine layouts by exploiting the statistical properties of layouts it progressively generates with improving performance. Considering that the turbines should be moved jointly, the algorithm models a joint distribution of the decision variables that represents the turbine positions. It then alternates between learning the parameters of the joint distribution from successful layouts and sampling entire layouts from this distribution.

Pseudocode for CMA-ES algorithm:

- Representation: Each turbine position is associated with a tuple of continuous x and y coordinates.

- For n turbines there are 2n decision variables. Let each decision variable be denoted as ti.

- Create a feasible solution. Initialise mi = ti for the multivariate normal distribution.

- Sample using a multivariate normal distribution N(m,C).

- Select a subset of best performing layouts.

- Update/re-estimate N(m,C) using the selected layouts.

- Go to Step 4 and repeat until satisfied.

Adaptation of the covariance matrix C in step 6 allows us to consider the relative positions of the turbines in the best layouts jointly. One of the advantages of an evolutionary algorithm (largely unexplored in the layout optimisation area) is that the energy capture calculations (which integrate wake effects) of candidate layouts (members of population) can be executed in parallel on modern multi-core or grid-based computers. Since CMA-ES works merely by adapting the multivariate distribution and then sampling from it one can perform steps 4, 5 and 6 on multiple compute resources.

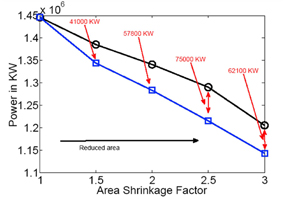

We use a modified park-wake model and we attempted to speed it up by converting all the operations involved in it into matrix operations. This way we were able to speed it up by a factor of 25 (180 seconds to 8 seconds for 500 turbines) while increasing the use of memory (due to storage of the matrices). To test the performance of the algorithm we conducted an experiment with 200 turbines. We set an initial area of 10 by 20 kilometres. As the initial placement for the CMA-ES, we divided the area into 200 cells and placed a turbine at the centre of each cell. We then reduced the area in successive steps by factors of 2/3, 1/2, 2/5, 1/3. We could not shrink the area any more since then we encountered violations even in the grid-based placement.

We ran a PSO which, when seeded with our initial placement in its first swarm, attempts to remove turbines if this improves the energy capture. We ran CMA-ES with Cartesian coordinates to improve the energy capture. Figure 1 shows the results of the two approaches. The blue line with squares is the PSO which works with a gridded layout. The black line with circles is CMA-ES. As area is reduced, we see a decline in the energy capture in both the approaches. This is expected since a smaller area implies more wake effects. However, the CMA-ES-based algorithm is consistently able to find a layout with higher energy capture. The energy capture improvement is almost equal to the wake-loss free energy capture of ten turbines (based on the wind resource distribution we assumed).

In another experiment, we optimised the layout of 10 to 100 turbines within a 3 square kilometre area with CMA-ES. We also optimised a layout of 100 to 1,000 turbines in an area of 200 square kilometres. For 1,000 turbines or less, with such a big area, it is interesting to consider energy capture gains as the turbines increase, but wake effects also become more dominant. Figures 2 and 3 show a progressively smaller increase in relative energy capture and a relatively larger increase in loss due to wake effects.

To summarise, an advanced evolutionary algorithmic approach learns the statistical properties of better candidate layouts and makes use of this knowledge to further improve them. For a problem ridden with constraints and a large amount of infeasible solutions in the search space it is paramount that we investigate techniques like the ones presented here to identify ideal solutions. Another effort should focus on how to parallelise these approaches efficiently to explore a vast search space. We have demonstrated the algorithm’s capabilities on problems involving hundreds and even thousands of wind turbines. As part of our current work we are investigating indirect encoding approaches to represent a layout and then employ a stochastic search algorithm.

Biography of the Authors

Dr O'Reilly is a veteran of more than fifteen years in the evolutionary algorithm community. She leads the Evolutionary Design and Optimization group at the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, MIT, USA. Her research currently focuses on evolutionary computation projects related to wind energy, sensory evaluation, computer systems (multi-core compilers and cloud virtualisation technology) and healthcare.

Dr Veeramachaneni is a post-doctoral associate in the Evolutionary Design and Optimization group at the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, MIT, USA. He specialises in PSO and cloud-scale, evolutionary algorithm-based machine learning.{/access}